Alamy

AlamyThey emerged from 1960s Detroit with an explosive sound that paved the way for punk. As a new LP is released, those who knew them explain how they changed the shape of music forever.

Detroit has a staggeringly rich history of music. From soul to techno via blues and garage rock, the US city has been a hub of innovation for the best part of the last century. While the sound of 1960s Detroit may have been dominated and epitomised by Motown, the era-defining soul label and production team, another band emerged in that decade who would help shape the sonic legacy of the city: the MC5.

Warning: This article contains language that some may find offensive

They are a group that have just been inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and who, a remarkable 53 years since their last album, have just returned with a new one, Heavy Lifting, as well as being the subject of a new book, MC5: An Oral Biography of Rock’s Most Revolutionary Band. However, the celebrations of their legacy and impact are deeply bittersweet, as the two remaining founding members – Wayne Kramer and Dennis Thompson – both died this year.

Their influence is vast. Loved by everyone from Motörhead to The Clash, they have been sampled by the KLF and covered by The Stranglers and The White Stripes. They were even the reason that Alice Cooper moved to Detroit to start a band. “There was nothing like it anywhere else in the USA,” he says in a quote on the biography’s jacket. Their sound, a fiery mix of hard rock, blues, free jazz, touches of psychedelia, and a blisteringly unique tone – complete with James Brown-like showmanship – would later have them called proto-punk, which is to say: punk before punk. Following Kramer’s death in February, Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello, who features on Heavy Lifting, wrote in an Instagram post that the band “basically invented punk rock”.

Alamy

Alamy“It’s just so wrong,” William DuVall, the Alice in Chains singer and MC5 collaborator, tells the BBC. “They’re finally getting into the Hall of Fame just in time for none of them to be here.” As tragic as it is that the band didn’t get to see their final album come out or to receive some long overdue adulation, their musical legacy is not going anywhere in a hurry. For those who fell into the whirlwind of sound spewing from the stage that was the band in full fury, it’s a difficult thing to shake off. “I’ll never forget going to see them,” musician and producer Don Was tells the BBC. “It was jaw-dropping – startling. I’d never heard, or seen, anything like that before.”

The Detroit dynamic

Was is a hugely successful industry figure, having worked with everyone from Bob Dylan to The Rolling Stones, and he grew up in Detroit in the 1950s and ’60s. “It was really vibrant,” he recalls. “After World War Two, workers came from all over the world to work in auto factories and they brought their cultures with them. So there was this crazy jambalaya of all these different elements. All those cultures then began to fuse together into something very original, and you can hear it in the music that came from the city.”

Aside from the multicultural and multi-racial backdrop that made up the city, its blue-collar roots also played a part in its inspired post-war musical output, Was believes. “There is something really honest about the people,” he says, “because Detroit was a one-industry town and everybody was in the same boat. So the music reflects that basic honesty. John Lee Hooker, to me, is the epitome of Detroit. The music is so raw that you almost think it’s about to fall apart, but it never does, and it grooves like crazy, and it’s as soulful as can be. So everything moves through that, from Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels to the MC5, The Stooges, and The White Stripes. They all come out of that tradition.”

However, Detroit was also a changing city. Manufacturing jobs from the auto industry were in steep decline, while tensions were in sharp ascent, culminating in the 1967 racial unrest. The co-author of their oral biography, Brad Tolinski tells the BBC: “If Motown represented Detroit’s aspirations in the ’60s, then MC5 reflected many of its brutal realities.”

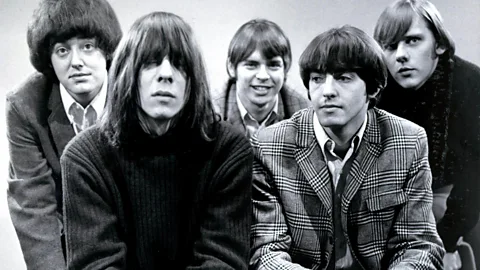

The band was formed in 1963 by guitarists Wayne Kramer and Fred “Sonic” Smith, and would go on to include Rob Tyner on vocals, Dennis Thompson on drums and Michael Davis on bass. As enamoured by John Coltrane as they were by Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry, in their early days the band were simply a flush-tight local outfit known to audiences for the power and precision of their playing. In an interview in Mojo magazine in 2003, Iggy Pop recalled seeing them during this period, when, as he said, they were a great “big city cover band”, who covered “real well” The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and The Who, among others.

The staunchly left-wing band also exemplified the counterculture movement of the 1960s, inspired as they were by Marxism and the beat poets, as well as the psychedelic drugs of the era. They became involved with local hippy, activist and jazz fiend John Sinclair, who became their manager. As anti-racists, they were avid supporters of the Black Panther Party and joined the White Panther Party, an affiliate political collective that Sinclair and others had dreamed up. “I visited their communal house where they had a Xerox machine down in the basement,” record producer Bruce Botnick tells the BBC, “where Sinclair was making copies of their White Panther Party political stuff.” They played anti-Vietnam demos that ended in riots, and soon they had a reputation as a band who were as sonically pulverising as they were politically charged – desperately seeking revolution on all fronts. On Gotta Keep Movin’, they sang, “Atom bombs, Vietnam, missiles on the moon / And they wonder why their kids are shootin’ drugs so soon,” while on The American Ruse they railed against the US’s “terminal stasis”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThey became both a representation and a rejection of the times, according to Jaan Uhelszki, the other co-author of their oral biography. “The MC5 took the cultural shifts – the Vietnam War, the race riots, the harassment of the longhairs – that were exploding in the US in the late ’60s and turned them into a subversive, reckless, thuggish art form,” Uhelszki tells the BBC, “full of high volume, high energy, rude flamboyance and a rough magic that seemed to release primitive forces in their audience.”

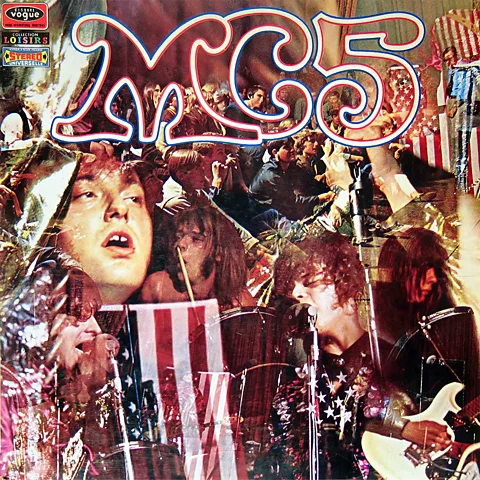

Danny Fields, who managed The Ramones and was working in A&R for Elektra Records, had seen the group, who were now playing more of their own material, and wanted to sign them. So label boss Jac Holzman, along with Botnick, went to check them out in Detroit. “It was the loudest thing I’ve ever heard in my life,” recalls Botnick. “Jac signed them instantly.” In a highly unusual, but very smart move, the band’s debut album was a live record. “We said, ‘This is where it’s at,'” recalls Botnick. “‘If we put them under studio conditions they’re just not going to perform because they need to be in front of their fans.’ The music didn’t lend itself to the studio – MC5 is a performing band.”

Released in 1969, Kick Out the Jams is not only regarded as one of the greatest live albums of all time but as a debut album vastly ahead of its time. It also captures a moment of pure crystallisation as a new kind of rock ‘n’ roll is being created. “It just sounded like everything was exploding all at once,” recalls DuVall of listening to the record when he was a teenager. “I could imagine the room having a hard time keeping itself together. I used to stare at the cover of the record in the same way I looked at comic books when I was a kid. I would just stare at the pictures because I wanted to be in the frame so much. It was almost like, if I stare at it long enough then maybe I’ll get some of that energy transfer.”

The album contained one moment that would go on to define not only the album but also the band. Along with a searingly powerful guitar riff, and a drum part so ferocious that it resulted in Thompson being nicknamed Machine Gun, the song Kick Out the Jams has an impassioned scream by Tyner. Before the track explodes to life, he declares: “Right now, it’s time to… kick out the jams, motherfucker!”

This did not go down well in 1969. Hudson’s, a Detroit department store, refused to stock the album due to such obscenities. MC5 and Sinclair responded by taking out an advert in local magazine Fifth Estate saying: “Stick Alive with the MC5, and Fuck Hudson’s!” This resulted in their records being removed from the shelves of stores nationwide, and the band being dropped by Elektra.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRather than being a blip, this was just the beginning of a tumultuous period. The MC5’s next record, 1970’s Back in the USA, followed, but so too did fallings out with Sinclair, who in 1969 had ended up with a prison sentence of 10 years for possessing two marijuana joints (although he was freed in 1972 after rallies and demonstrations, including support from the likes of John Lennon). Drug use became a problem in the band, too, with heroin creeping in by the time of 1971’s aptly titled High Time. New Year’s Eve 1972 would see them play at Detroit’s Grande Ballroom, a venue which just years earlier had been bursting with thousands of screaming fans, and was now sparsely attended. Kramer left the stage halfway through, utterly distraught, and the band ended.

Their eventual reunion

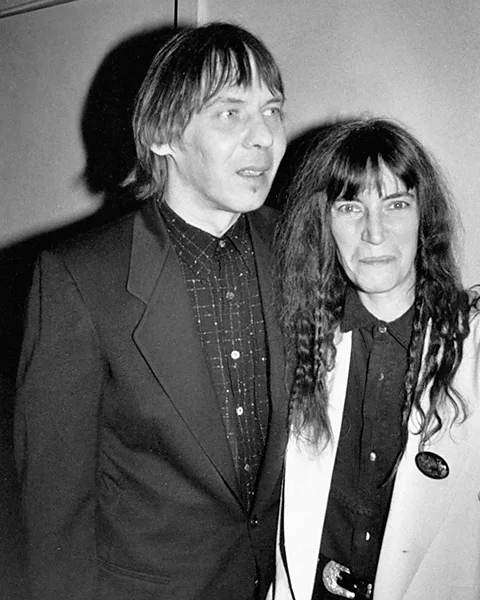

Kramer and Davis both ended up in prison on drug charges, while the other members formed different groups and went down different roads. It would be 20 years before they got back together in 1992 to honour Tyner after his death the previous year. Sadly, Smith – who in the intervening years had met and married punk icon Patti Smith – would die in 1994. But as the years went on, the band’s influence and impact were more noted and celebrated, and there were reunion tours featuring all three surviving members – Kramer, Thompson and Davis – plus a variety of guest vocalists, including DuVall. “It was utterly surreal and magical,” DuVall says of the full circle moment of getting to play with his heroes. “It’s hard to even put into words what it meant for me.”

Similarly, guitarist Gilby Clarke, who had been a member of Guns N’ Roses, recalls how special it was to play the MC5’s music to a newly appreciative audience when he was in the band from 2005 to 2012. “It was done purely out of love,” he recalls. “And when Wayne showed me the guitar parts, it blew me away. It totally gave me a new appreciation for the music, and to see how he and Fred really planned out those parts, and what really made that MC5 sound, it was just astonishing.”

Davis died in 2012, and Kramer, Thompson and Sinclair all died between February and May 2024, just before the band’s swansong was due to come out. Heavy Lifting was produced by Bob Ezrin (Lou Reed, Alice Cooper, Kiss). Thompson features on two tracks while Kramer co-wrote 12 of the album’s 13 songs with the Oakland singer-songwriter Brad Brooks. Because Kramer had worked so actively and passionately on the new record, his death from pancreatic cancer was the one that came as most of a shock. “Nobody saw that coming, least of all Wayne,” says Was. “He really thought that he was okay until about 10 days before he passed. He had big plans for this year and for this record.”

Was plays bass on the record and feels that it is a joyful parting statement. “It’s a beautiful memory for me,” he says. “Our mission was to play at maximum energy to reflect the spirit of the original band and I’m really glad we got the chance to do it. And also, I’m proud of Wayne. He went out in top form. I think it’s the best record he made.”

Margaret Saadi Kramer

Margaret Saadi KramerDespite originally breaking up just as punk was around the corner, the band’s prescient high-octane assault has proven endlessly influential. “The reason we describe the MC5 as ‘Rock’s Most Revolutionary Band’ in the book is because they actually were,” says Tolinski. “They pioneered the sound of heavy metal and the defiant attitude of punk rock.” However, Was still feels that their impact is overlooked in the grand scheme of things. “Their legacy needs to be elevated,” he says. “They were the most revolutionary, radical and rebellious of all groups – they captured the real essence of rock ‘n’ roll.”

MC5’s Heavy Lifting (earMUSIC) is out now