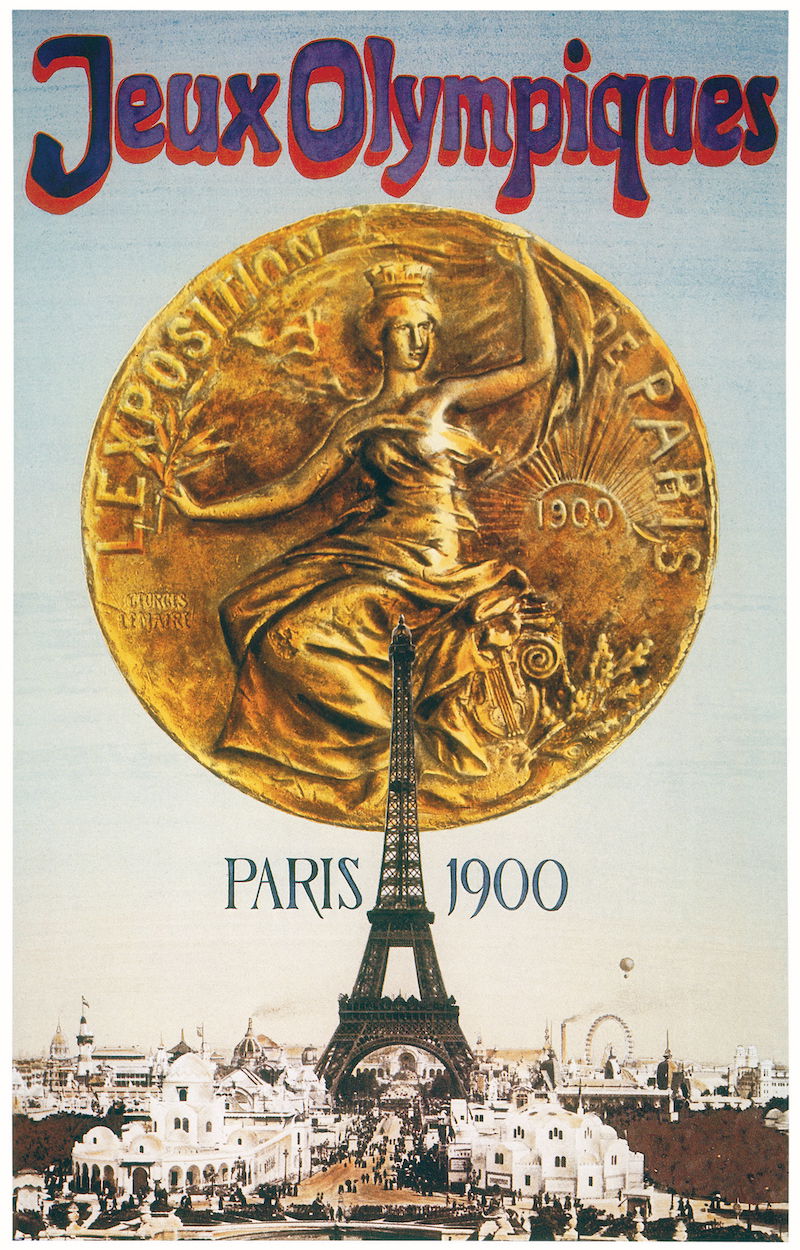

This year’s Paris Olympics are the third to be held in the city – where the decision was made in 1894 to revive this ancient Greek event – but the first for exactly 100 years. After paying homage to the Olympics’ origins by entrusting the first modern Games to Athens in 1896, the newly formed International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided that the second – and the first of the new century – would take place in Paris in 1900.

At this time Paris was teeming with ideas, whether artistic, scientific or industrial. This ferment of innovation was epitomised by the world’s fairs, where the masses came to marvel at the new and to wonder at humanity’s ingenuity and growing mastery of the world around them. An Exposition Universelle had already been earmarked for Paris that year. The 1900 Olympics duly became an adjunct to this, with the French state able to elbow aside the stripling IOC and shape the Games in line with its priorities of economic and military strength.

The result was a grand enterprise. Events took place over five-and-a-half months, from mid-May to late-October. There were almost 59,000 participants. These included athletes, swimmers, cyclists and fencers from around the world. But the ranks of competitors also encompassed well over 7,000 firefighters, 3,000 first aiders and 600 anglers. The programme was fixed by a web of committees under a grand commission established by the French minister of commerce.

The story of this quite astonishing festival of sport is outlined in a dense 795-page official report, bearing the heading of the French Ministry of Trade, Industry, Postage and Telegraphs, as opposed to any Olympic body, and produced at the Imprimerie Nationale, responsible for printing official documents. The picture that emerges is of a sprawling competitive sports spectacular very much at the service of the French nation. First aid and firefighting had obvious social utility. But even the angling contest, staged on the banks of the Seine, was justified in part by a need to cut the bill for freshwater fish imported from other countries.

With new technologies advancing at a rapid pace, not least in the fields of transport and warfare, the Games provided an opportunity for testing performance levels in demanding conditions. Motorsports formed an extensive part of the sports programme, with events including reliability tests for hackney carriages, delivery vehicles and even heavy trucks, whether hydrocarbon-, electric- or steam-powered. There was also a gruelling long-distance race from Paris to Toulouse and back, a distance of some 1,400km.

The relevant section of the official report is laden with technical details about mechanisms deployed by the competing machines, along with photographs, in a manner more in keeping with a motor show than a sports event. There is also the occasional explicit reminder of the seriousness of purpose underlying the contests. ‘One might be inclined to think that a small motorcycle (“motocyclette”) is a simple toy’, notes the report.

‘However, an artillery commander … affirmed that with a skilled mechanic an officer used to riding tandem could easily circulate quite rapidly on a road where a motorcycle could not pass.’

A preoccupation with military applications and national defence is frequently apparent, perhaps not surprisingly with the disastrous Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 well within living memory. The cost of the many target shooting contests outstripped that of any other sport. There was, in addition, a competition for 90mm cannons, for French nationals only, conducted with no spectators present. Shooting is described in the report as ‘a sport so noble and so important for the very existence of our dear country’.The document also includes extensive remarks made by General Jean Tricoche, with reference to the Second Boer War then raging, to the effect that the pace of innovation in weaponry was such that frequent practice by men who might be called upon ‘if war comes to surprise us’ was essential.

Another feature of the 1900 Olympics was a staggeringly ambitious nearly four-month-long series of balloon competitions. These tested how high, far and accurately competitors – largely French – could travel amid the changeable winds of the Paris region. Some of the incidents befalling these intrepid balloonists might have been taken from a Jules Verne adventure story. On touching down in rural Ain, west of Geneva, one contestant, recorded as ‘J. Faure’, was ‘taken for an English spy’. On another occasion, Comte Henry de la Vaulx’s balloon was assailed by a nocturnal storm that saw it touch speeds of over 100km an hour. ‘I think it was a miracle that we escaped death’, noted the balloon’s log-book.

The most extraordinary happenings of all were reserved for the last balloon race of the Games, with competitors setting off from Vincennes on 9 October with a full moon in prospect. Remarkable distances were covered, with the leading contenders traversing Germany and reaching into eastern Europe. The runner-up, a Monsieur Balsan, who finally touched down in south-central Poland, found himself flying low enough at one point to ask for directions. He was answered by rifle shots. The winner – de la Vaulx – kept going and going until he touched down not far from Kyiv, more than 1,900km from Paris.

As with the other sporting events at the 1900 Olympics, ballooning had a military application; as the report bluntly reminds us, balloons, too, ‘are a war tool’. Aviation was, moreover, about to emerge as the next transformative new technology. As the official report put it:

‘The 1900 “aérostation” competition has given a fresh impetus to this general movement … It has contributed significantly to knowledge of the medium which we must now definitively conquer.’

No doubt today’s French politicians will hope to benefit from the burst of patriotic pride that the Olympics often engender. But when it comes to putting sport at the service of the nation, the 1900 Games are unsurpassed.

David Owen is the author of Aux Armes! Sport and the French, an English Perspective (Forward Press, 2024).

575 Comments