Have you ever wondered how the results of scientific research get written up, published, disseminated and, in some cases, eventually accepted as conventional wisdom? How do those obscure academic articles in hard-to-remember journals contribute to our everyday understanding of the world around us? Are you perplexed over how science says one thing today only to be upended tomorrow?

If so, you are not alone. Scholars and scientist have been struggling with how to ensure quality and rigour and how to deliver the best knowledge possible for centuries. The difference now is that we have better tools to help sift through and assess what has become a veritable tsunami of ‘knowledge’.

The principle of ‘free’

The Kiss, René Magritte, 1951, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Photo by Rob Corder via Flickr

Open Access (OA), which is free to the reader at the point of use online, sits in the middle of all this. While costing nothing to the user, this does not mean, however, that it is free to create, publish and deliver to those who want to read it. It does not mean unrestricted use of the content. It definitely does not mean the end of copyright, as some surmise. Nor is it primarily a social movement.

The approach is best defined, in OA godfather Peter Suber’s words, as ‘a set of principles and a range of practices through which research outputs are distributed online, free of access charges or other barriers’. It is a child of the digital revolution. Conceived by a handful of scientists in the biomedical field, it was meant to address the issues of inequitable access to research findings perpetuated by traditional, large commercial publishing companies replicating old print business models, charging high prices for closed digital editions. Arising from a small meeting in 2001, the Budapest Open Access Initiative became the founding declaration and provider of initial guidelines to make research free and available to anyone with Internet access – initially to promote advances in the sciences, medicine and health.

Since those early, heady days, activists who have campaigned for OA can now claim partial success. Statistics vary and yet, according to the Directory of Open Access Journals, nearly 21,000 journals carry some open access articles. DOAJ holds records on just over ten million articles. Getting to this point was a considerable struggle, however, as new business models had to be first tried and tested. Adoption of OA varies by discipline, publishing traditions and availability of funds. But make no mistake, this is a huge number from a vast business that according to STM produces over two million journal articles a year, in a market worth over US$20 billion.

Early activists argued for OA on moral grounds. It was unfair to continue to privilege those scientists who were working in high-income countries while institutions in low-income countries or even those less wealthy in high income countries could not afford journal subscription fees. Various studies were commissioned, one of the most important being the 2012 Finch Report from the UK, which argued that ‘publicly funded research should be publicly available’. In the UK some enlightened Ministers began to see how being ‘open’ might benefit the competitiveness of companies located in their jurisdictions. OA was moving mainstream, though not without rearguard protests, especially, but not only, from scholars in the Humanities.

By 2015 the influential Crossick Report looked at scholarly monographs and OA, a format used more extensively in the Humanities and Social Sciences than the hard sciences, often referred to as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths).

Governments and independent funding agencies began ascertaining their policies on OA. Importantly, developmental policies required mandates. And, all the more critical, funding needed to flow, following one or more business models, to enable sustainable open access – a high-level challenge differing from country to country, funder to funder, publisher to publisher.

OA funding needed to be rechannelled from existing budgets. If content was to be free, how would publishers be recompensed for their work? No longer able to rely on subscriptions to gated journals, new business models needed to be created to enable this new development.

Nonetheless, it was generally accepted that if scholarly journals and monographs had been successfully sustained in the old world then the issue was not so much needing to find new money, but rather how to reallocate existing funds. Some creativity was needed.

One of the most famous, early approaches was the German DEAL, a consortium that introduced the concept of ‘publish and read’, whereby research institutions banded together to pay a flat fee to a publisher. In exchange, publishing for their scholars was free of charge in open access mode. That set the stage for ‘transformative’ agreements between libraries and publishers. Another facilitator of OA was Knowledge Unlatched that created a marketplace for various business models. Both rested on the assumption that collective action on the part of institutions and their libraries could redirect sufficient old subscription money to making content ‘open’. Afterall, if the cost to the subscribing libraries was not more than before, what was there to dislike?

Creative Commons licensing

How to protect copyright in a digital world where content is given away for free became a sizeable issue. Back in the early 2000s, a group of lawyers at Stanford University, California, came up with the idea of licensing content on the Web on a ‘some rights reserved’ basis, which acknowledged the original copyright owner and limited certain user rights (e.g., restricting commercial use and/or derivatives). They called these authorizations Creative Commons (CC) licenses – denoting the idea of creating a ‘commons’ where people not only could benefit from OA but also were able to develop work from originals.

This was of particular interest to musicians who were creating mashups and wanted acknowledgment for their resultant work. In his book Free Culture, CC founder, Lawrence Lessig, writes ‘the goal is to counter the dominant and increasingly restrictive permissions culture that limits artistic creation to existing or powerful creators’. CC licenses were developed to cover all creative works and not just scientific articles. Today, well over two billion items are tagged with CC licenses.

Has CC been effective? Can’t people cheat? Well, yes, and a few have been prosecuted through the courts – successfully. But most people don’t cheat. They abide by the terms, much to the benefit of the creators and the whole world. And CC licences are also being used just as successfully in OA scholarly content. It is amazing just how effective CC licensing has been.

Gold, green and diamond access

From time to time, the value of the Internet and the ability to make content open come together in dramatic, beneficial ways. Within weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic most international publishers opened up access to all their research content. What happened then was truly amazing: thousands of researchers were able to access research findings that in turn helped to speed up the development of COVID-19 vaccines, saving countless lives.

While not staying open forever, students did benefit for a limited period when they had access to an unprecedented amount of content. It was as if the world’s largest libraries had come together and gifted their collections to the world – an act of generosity in the spring of 2020 as individual libraries were figuring out how to serve their constituents while the doors to their buildings remained firmly shut. But the content was mostly on loan, not a permanent gift – and, therefore, not truly OA.

However, this period led to publishers adapting their business models to what is now referred to as ‘gold OA’, enabling an article or book to be made OA upon publication, usually with a fee, paid for in advance, to cover publishing costs by either an author’s institution or grant funder. Another model called ‘green OA’ was developed in parallel, whereby an article can be made open through any platform either in its earlier pre-publication form, and/or after an embargo period (typically between 6-12 months after formal publication). Peter Suber outlines a further distinction between the two: ‘There are two primary vehicles for delivering OA to research articles, OA journals (“gold OA”) and OA repositories (“green OA”). The chief difference between them is that OA journals conduct peer review and OA repositories do not. This difference explains many of the other differences between them, especially the costs of launching and operating them.’

In the journal world these fees are called Author Processing Charges or APCs, while for books they are called, unsurprisingly, Book Processing Charges or BPCs. ‘Transformative deals’ were made between publishers and libraries, whereby libraries redirected subscription money to pay for the publication of faculty articles in what became known as ‘hybrid’ partner journals. The intention, over time, was that all academic published articles covered by such deals would be gold OA. However, by some estimates, including that at Jisc, the UK digital, data and technology agency serving tertiary education and research, it would take 70 years before all journals flipped entirely to OA.

While there are now over 1,000 such deals, covering tens of thousands of journals, consternation soon set in regarding a system that privileged wealthy institutions. Readers benefited, but publication barriers remained for authors at less financially stable institutions. Other distortions also surfaced, including the incentivization of an increasing number of articles. As a result, a diamond version of OA publishing has recently emerged: namely, scholarly publication models in which journals and platforms do not charge fees to authors or readers.

Of course, the cost of publishing under the diamond model still has to be covered somehow, encouraging a myriad of new non-APC models, whereby the cost of publication is not linked to a specific article or book. Some are based on collective actions by libraries to agree on jointly keeping journals open access such as the Subscribe to Open model, which is just beginning to gain traction. Another is for individual institutions to own and manage their own journals and commit to covering costs. None of these solutions are free of complications.

Pressures from funding agencies have simultaneously coalesced around Plan S and its ten principles. ‘With effect from 2021,’ proposes the initiative, ‘all scholarly publications on the results from research funded by public or private grants provided by national, regional and international research councils and funding bodies, must be published in Open Access Journals, on Open Access Platforms, or made immediately available through Open Access Repositories without embargo.’

While this plan accounts for grant-funded research, many articles in the Humanities, for instance, do not arise out of this system. How to make OA viable in all disciplines presents an even greater challenge – a long road with many twists and turns. Policies are easy to write and agree on, mandates are harder to find consensus on, but the real problem is redirecting funding from pots that are jealously guarded for a status quo that works well for some but not others.

Understanding ourselves and the environment

Preserving research integrity is also a significant aspect of current OA debate. Isn’t commercialized OA as funded by APCs leading to more cheating and more unnecessary publications, indeed a booming ‘paper mill’ industry, where nefarious businesses produce poor or fake research papers that look like genuine research?

Which system is the best at assessing quality is also heavily debated. Publications are often a proxy for quality. Promotion boards rely on their reputation. Older journals functioned well in the past with their closed models. And newer, genuinely high-quality OA journals have to establish their credibility to compete against the old guard on the one hand and paper mills on the other.

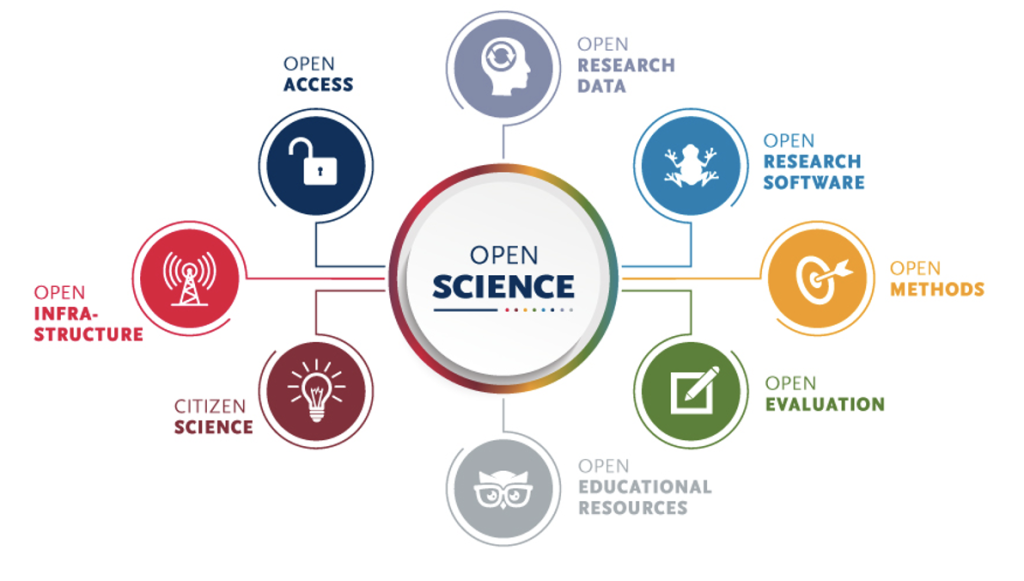

OA is part of a newer, broader movement that has a commitment to making all aspects of scientific research, not just the final articles, open and available to the public at its core. This approach is known as Open Science, including Open Data. And the discussions around these concepts are even more complex than OA. This diagram from the University of Potsdam illustrates this point simply and shows where OA to publications falls in the open science cycle.

Open Science cycle diagram, University of Potsdam

Here we see open research, beginning with raw data, being processed by research software. Research methods are made transparent and the evaluation of findings are posted openly for all to understand. Where appropriate, open educational resources can be created from the research findings for learning and instruction. The citizens science element encourages active public involvement to foster trust in scientific research. Open infrastructure refers to the technical scaffolding necessary to ensure discoverability and accessibility. Then, at the end of the cycle, we see a commitment to open access, which is imperative to opening up science to the world.

We are currently in the middle of a complex and long transition where ultimately most, if not all, research will be available to fellow scholars and scientists, students and even the general public – all around the world. And we haven’t even touched on how AI will impact openness here. Suffice to say that in these early days of generative AI and large language models (LLMs), the new technology’s challenges and opportunities are being assessed for major national and EU legislation.

If you find all this baffling, you are not alone. The President of Oxford University Press USA spends most of his time assessing what is happening in the tech space and what this means for OUP’s content. One thing is certain, we are in the midst of a fundamental revolution around what should be open, what can be open and how to make it open. There is some urgency to this, as we need to speed up our understanding of ourselves and our environment.

Open Climate Campaign is one interesting example underway following the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The project brings OA activists and environmentalists together to promote policies, mandates and funding to make all research around climate change and biodiversity open access. The project is a Creative Commons initiative partnered with SPARC and EIFL. It is unique in the way in which it focusses on a set of substantive issues and then provides stakeholders with tools and training to find new ways of making more and more content open access.

While the objectives of OA are clear, the means to making it a reality can be subject to ill-tempered political and ideological debates. They can obscure and complicate the routes to achieving access for all. Fortunately, there are enough people willing to experiment with new models that are bringing us closer to realizing truly fair and equitable OA goals.

This article was commissioned as part of Come Together, a project leveraging existing wisdom from community media organization in six different countries to foster innovative approaches.